Choosing the Right Tactics for the Fire

When deciding upon a course of action on wildfire, you should be aware that not all of the apparent opportunities from which to launch an attack are suitable. Many accidents happened because someone ignored the predictable fire behavior potential.

It is a good fire supervisor who understands that firefighters may have to change the original plans to match the fire behavior predictions made by them while on the fire line.

Under low intensity fire conditions, a downhill direct attack might appear a good control opportunity. But if the direction of the fire intensity is increasing to over-threshold behavior, it is a poor choice or at best a good tactic applied at the wrong time. A time tag is needed to end the direct attack suppression effort BEFORE the over-threshold fire behavior event occurs. (There is a general rule to avoid downhill line construction; but downhill line construction cannot always be avoided.)

Fire Behavior Tactics versus Opportunity Tactics

There are two types of tactics used in firefighting: the opportunity tactic and the fire behavior tactic. The opportunity tactic only requires recognition of when or where a suppression effort could be launched. The fire behavior tactic, on the other hand, is a tactic selected due to the predicted behavior, intensity or rate-of-spread of the fire at the time and place of the action.

You should keep in mind which tactic you are engaged in. Is it the OPPORTUNITY TACTIC or the FIRE BEHAVIOR TACTIC?

Fire behavior tactics need to be considered to assess the success probability of the opportunity tactic. Many firefighters have been burned over on good opportunity locations during the worst fire behavior periods. The fire behavior character of the wildfire may rule out some opportunities for periods of time. Be sure to identify these situations and recognize them.

The Incident Action Plan tactics may need revisions during your operational period. When should you re-evaluate the plan?

Some fire accidents can be directly attributed to the pursuit of a fire suppression plan that was not revised upon the receipt of relevant fire prediction information.

If the fire has been backing down slope toward your location all day and you are on a tractor line that is located away from the edge of the fire (called an indirect line) with a wind forecast that predicts the wind to blow the fire towards you, the opportunity tactic should be changed to a fire behavior tactic before the fire overruns your line.

This was a planned tactic that was appropriate until the wind forecast was available. Such were the circumstances on the Romero fire near Carpentaria, CA. Four firefighters were burned over because they continued to implement a tactic that had run out of time.

Tactics need to be tied to Conditions

This concept recognizes that the tactics must be suitable to the conditions. When conditions change or are forecast to change, the tactic should be evaluated to determine whether it is appropriate to the new condition.

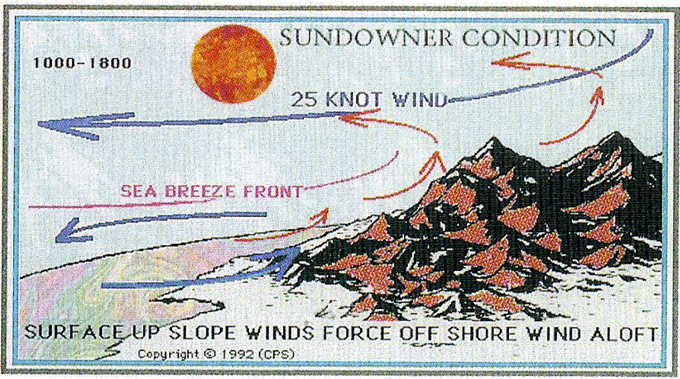

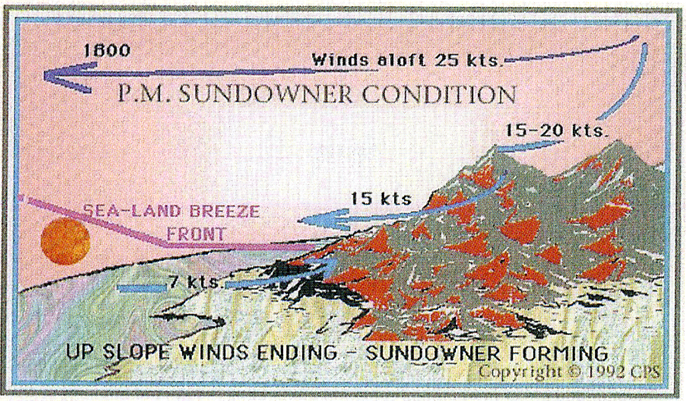

An example: fire crews building an indirect fire line are ordered to fire it out after completion. The time to construct the fire line is estimated at eight hours; it is the day shift. At the start of the shift, the fire behavior situation favors the suppression crew. The fire is burning against the alignment of forces, backing into slope and wind toward the crew. But a weather forecast predicts a wind shift of a strength that would turn the fire into a wind-driven fire, overcoming slope effect. Sundowner winds are also forecast. It is your job to determine if the indirect tactics remain valid for the new forecasted condition.

Such a major change in alignment and strength of the wind dictates a re-evaluation of the tactics and a determination of when the tactic should change. If you elect to wait until you are run out, it may be too late to avoid a burn over incident.

Changes in suppression tactics may be based upon a forecast and action taken before the fire behavior changes. When called for, it is helpful to a supervisor to hear the phrase, “the current assigned tactics do not match the forecasted conditions.” After alerting the supervisor to the situation, you may suggest tactical adjustments that agree with the forecasted conditions.

A road that would make a ready-made fire break and can be used for access for a frontal attack is an opportunity, but the question to ask is “Will that tactic be appropriate for the expected fire behavior during the suppression action?” If I were assigned that opportunity and I expected the fire behavior to beyond the threshold during the attack, I would call the operations chief and use some appropriate phrases listed in Chapter 6 to revise my supervisor’s expectations. If I got that assignment, I would appreciate the tactic be time tagged for the period “going down the flammability curve.”

Tactics Based Upon Fire Behavior Predictions

Which way is the fire intensity going, up or down?

It is important to keep in mind the fire behavior potential. Is it getting worse or easing? Are the fuels in the path of the fire becoming more or less flammable?

I have seen fire suppression tactics continued that was in total opposition to the predictable fire behavior. This occurs when people doing the work fail to realize the change in fuel flammability and the potential increase in the fire’s intensity.

On a control burn project in Kern Canyon on the Sequoia National Forest; the firing crew was burning out the fuels below a road. The fuel was grass and medium brush with an occasional bull pine mixed in.

The exposure was Breckenridge Mountain, a long steep slope with a west aspect. As usual, the morning burn started slow but increased to reach very acceptable intensities just before noon. Shortly after noon, the prescribed fire spotted above the road.

This is the time when you should ask: Is the flammability going to worsen between noon and 4:00 p.m.? Yes, it is; it’s going up the flammability curve.

The crew controlled the spot fire above the road and began firing again in an attempt to finish it off. The fire spotted again, but this blaze was not so easy to control. It was about 2:00 p.m. as I recall, when the fire reached threshold behavior, starting more spot fires than the crews could contain. It escaped all efforts to stop it and ran to the top of the mountain. The result was a project fire originating from a prescribed burn. Was the fire’s escape potential predictable? It was if you accept the important factor of fuel flammability.

The west aspect peaks in flammability about 3:00 p.m. sustaining high intensities until after 5:00 p.m. Firefighters who add fire at the base of a hot slope exposure when spot fires have already occurred, fail to foresee the results of the act. The cost of that error was substantial.

Another example I’ll offer is the situation during a project fire that was caused by a careless camper in the Sequoia’s Kern River Canyon. The fire started at the base of a southwest slope in the afternoon on a hot summer day. By noon, about 800 acres had burned.

A spot fire started at 4:00 p.m. in the rocky river-bottom growth about 400 yards from the burned slope. The flats were cooling off by this time; a hand crew and dozer, with the help of some helicopter water drops, caught the fire at about an acre.

The Operations Chief, Marv Stout, ordered the dozer and a small hand crew to remain throughout the night. The orders for the day shift covering the spot fire was to remain through the heat of the day and mop up any smokes in the burn.

The day was extremely hot. Temperatures were over 100 degrees in the fire area. At about noontime, the sweltering crew supervisor assured the Incident Commander that all was well on the spot fire.

The Commander gave the OK for the dozer and crew to walk out of the river bottom.

Now, those river bottom flats were just about as hot as they could get when the dozer clanked through the rocky brush-covered area headed to the staging area. The tracks were slipping on rock, shaving metal flakes that were blue with heat from the friction.

Tactics should match the observed and predicted near-term fire conditions.

It is critical for a supervisor to effectively match tactics to conditions so that he/she can maintain the relative safety of their crews. They must be able to predict fire behavior changes and amend existing tactics when the situation demands.

Just like a Boy Scout starting a fire with flint and steel, hot metal shaved from the tracks started another fire. At this point, the flats were at the peak of the fuel flammability curve. Like they say, “We saw the enemy and it was us.” The fire burned about 300 acres alongside of the 800-acre fire before it was controlled. The only good news was that with a fire camp already established, the main fire was controlled and the suppression forces were in place.

How could this have been prevented? Easy, just walk the cat out when the fuel is cooler and less flammable. As you can see, small oversights can became costly.

A Few Basic Rules about Tactics Selection

Tactics selected for implementation should be based upon a prediction of success. We should not fight fire without making predictions of success, or we will be fighting fire only for the thrill of the battle. Unsuccessful attempts at fire suppression should be considered an error in judgment.

As I look back on my firefighting days, I realize that I often acted without sufficient regard for the fire behavior potential.

Opportunity tactics are appropriate:

When the fire is stable and when the behavior variables are below the threshold of safe control.

Fire behavior tactics are needed:

When the behavior variables may exceed the safe control thresholds.

When selecting tactics take into account the lessons of yesterday. Did the tactic work previously under similar circumstances? If situations arise where conditions are out-of-phase with tactics, accidents can (and do) happen.

Understanding How Tactics Are Developed

We will first examine how the tactics are developed that are written into the Incident Action Plan for large project wildfires.

When the initial attack fails to stop a wildfire, most fire agencies prepare a plan of action for the incident. This plan is called the Incident Action Plan. The incident Action Plan spells out the situation, the organization, the resources, the chain of command and more. Planning is begun hours before implementation, on project size Forest Service wildfires.

All who participate in larger wildfire incident suppression work should understand the lead-time that the functional units of operations, logistics and plans require to do a good job. Some of the details that must be accomplished prior deploying fire crews are:

- The fire perimeter must be projected and displayed on maps to be used by following shifts

- The resources (firefighters, engines, aircraft, food, transportation and so on) need to be identified and given some time to assemble and prepare

- The Incident Commander and staff must assemble and present information, prepare strategies and come to timely agreement to enable preparation of the Incident Action Plan

Once the Incident Action Plan has been reviewed and approved, a briefing is held. Assigned overhead attend the briefing, survey the plan, gather their respective resources, and move into their assigned position. During the operational period, they will re-assess the situation on their portion of the fire line to ensure the conditions remain compatible with the actions set forth in the Action Plan.

Only then will experienced overhead initiate the tactical plan. The firefighters executing the plan need to understand the critical need for timely planning, even though circumstances may change during their operational period.

It is dangerous to become tactically inflexible when fighting wildfires. Continuing indirect line construction when conditions are worsening can cause burn over accidents.

Disaster can stalk fire-fighting units that continue to use tactics that are no longer safe because of a change in conditions. Just because the tactics were written in the plan it doesn’t mean that the firefighters must continue a tactic that becomes unproductive or dangerous. The supervisors on the fire line often must make tactical changes because the conditions have changed during the operational period.

Planning a Typical Night Shift

In order to better understand why some fire assignments fail or sometimes result in tragedy, let’s look at how the plans carried out by firefighters are concocted. Following is a sequence of events that occur when a typical night shift is planned.

The day shift firefighting units are on line at 6:00 a.m. assessing the assignment; they are beginning their 12-hour work period on fire lines.

Sometime between ten o’clock and noon, the Incident Command Overhead must start the planning process for the night shift plan operational period. This plan will be used to identify night resources, assignments, and provide information and objectives. Projections of the fire line that were constructed and held, the escape potentials and the projected situation at 6:00 p.m. this evening must now be made. The overhead personnel assigned to the fire must use their experience of fire behavior and suppression capabilities to provide the needed estimates.

Before the day shift is half over, Operations must develop the necessary information in order to efficiently deploy the resources and develop tactics for the night shift. The Operations Chief should sketch the probable location of the fire edges between 6:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. the following day. Next, the amount of fire line that will be constructed and held during the day shift is estimated. The Operations Section Chief may ask the overhead for their assessment of the situation which the night shift will confront in the next 24-hour period. It is possible that the Operations Chief would ask the Division Supervisors for a recommendation of resource commitment for their sections of the fire line; or the Operations chief may prefer to do the resource ordering/planning for the next shift without other input.

If the fire line is constructed and the fire contained, it is simple to plan the next shift. But when fire lines are failing to contain the fire spread, it is not so simple. The Operations overhead assigned must be willing and able to predict the tactical situation six hours in advance of the relief crews’ arrival.

At 1:30 p.m., the Incident Commander and staff hold a planning meeting to hear the General Staff’s input and to approve plans for the next operational period. The Incident Commander approves the input for the night shift Incident Action Plan at about 2:00 p.m. Personnel from Plans complete the resource order forms and check to ensure that adequate resources will be available. If additional resources are needed, orders to obtain them are initiated.

The General Staff submits their written plan to the Plans unit within the hour. The Plans unit makes copies of the night shift Incident Action Plan in sufficient numbers for distribution. At 5:00 p.m., the night shift overhead personnel are called together for their briefing and given the night shift Incident Action Plan. A half-hour later, the line supervisors assemble and report to their assigned locations to begin their fire-fighting shift. This planning process works best when the overhead estimates are accurate. Estimates are most accurate when the fire situation is stable.

The significant point to this story, however, is that the Incident Action Plan tactics are inherently weakest on the sections of the fire that are changing or uncontrolled. Those firefighters involved in the implementation of the plan must reassess the situation and change the plan as necessary. Failing to compare the current or real situation to the situation projected in the shift Incident Action Plan is a serious omission. When there are differences between the plan and the fire ground, actions taken without the benefit of this comparison may result tragically. When the plan does not reflect the real situation, the firefighters must re-evaluate the situation and use initial attack procedures even though they must deviate from the plan. This situation might occur at the beginning of a shift, or at any time during the shift.

General Staff Timetable

| 6:00am – 8:00am | Progress reports and 24-hour plan for control |

| 8:00am – 10:00am | Gather information for Night Shift Plan |

| 10:00am – 1:00pm | Rest period |

| 1:00pm – 3:00pm | Obtain details for night shift; complete Night Shift Plans |

| 3:00pm – 4:00pm | Intelligence reports require adjustment in Night Shift Plans |

| 4:00pm – 4:30pm | Briefing with night shift overhead |

| 6:00pm | Resources change shifts; staffed of night operational period. |

The significant point to this story, however is that the Incident Action Plan tactics are inherently weakest on the sections of the fire that are changing or uncontrolled. Those firefighters involved in the implementation of the plan must reassess the situation and change the plan as necessary. Failing to compare the current or real situation to the situation projected in the shift plans is a serious omission. When there are differences between the plan and the fire ground, actions taken without the benefit of this comparison may result tragically. When the plan does not reflect the real situation, the firefighters must re-evaluate the situation and use initial attack procedures even though they must deviate from the plan. This situation might occur at the beginning of a shift, or at any time during the shift.

Fire Supervisors Must Know

the Capabilities of their Resources

Preparing yourself to become a qualified supervisor to oversee fire suppression work is important. Supervising crews, aircraft and equipment engaged in the act of fighting wildfires is certainly complex. Supervisors should be capable to get the most from their resources without overextending them. This requires at least a working knowledge of the capabilities of the resources.

What background is needed to become a quality wildfire officer? There are two important steps: One is familiarization with the resource capabilities you may have occasion to supervise. The second involves observing and learning from wildfires.

Familiarization of available resources is paramount in managing the assets of a fire agency. How much fire line can hand crews construct in different fuel types under adverse weather factors and terrain conditions? How much fire line can an engine crew hold under varying conditions and terrain? What are the capabilities of the D-6 bulldozers in unfamiliar terrain?

Training crews in firefighting drills is one of the best ways to learn the capabilities of the crew and their equipment. You can use this practice to develop the skills to enable you to effectively estimate work capability. You can also learn by observing on fires. It may take years before you are drill proficient but even that is not the end of it. Chuck Mills, once a burn over victim himself remarked,

“We spend all of our time training to understand what we can do to fires, and little time on what the fire can do to us.”

To become a fully proficient wildfire officer, one must acquire the knowledge and skills to be able make fire line fire behavior predictions, and communicate the cause and effect to others.

Preparing to become wildfire proficient requires additional time investment and the development of specialized skills. The path from a drill instructor-type fire officer, to a proficient wildfire officer is usually a long and perilous trek. During the journey, you will face new fire situations in random order of severity. In this happenstance, you will be given increasing authority and responsibility.

You may never “catch up” enough to feel ready for the next big one. It seems that many firefighters spend their entire careers with that feeling.

The next proficiency that one should acquire is that of knowing what will change. I have been in situations when a fire officer gave orders to evacuate the area. He had seen danger ahead and reacted with the order. Many firefighters never know what these men see or how they predict fire behavior changes. How many times would you have to experience something like that before you realize that until you learn the art, you are at risk? Why didn’t that firefighter tell me what caused the fire to blow up and how he saw it coming?

The Technical Side of Firefighting

Now is the time that the academics of fire physics, fire behavior, weather, topography and fuels should be utilized to enable you to predict what factors are about to change in the fire situation. As you progress in the application of this knowledge on the fire line, you should develop the skill to observe the mix of forces acting upon the fire, and be able to predict the result. Supervisors should develop the skills to be able to relate the cause and effect of the natural forces where they work. If you cannot look at a location that will burn in the near future and predict the fire behavior change that may result, you are not yet proficient as a firefighter.

During the time that firefighters are on the line, the situation continually changes as the position of the crew in relation to the fire changes. The topography on which the crew is working changes as the crew moves, and the fire behavior changes. This evolving situation is very different from a drill on the local football field.

Many firefighters depend upon their ability to react in time to a fire behavior change their reaction time is their only safely margin. This is a dangerous and sometimes deadly practice. It is greatly preferred to foresee changes in fire behavior. Then you have additional time and time is protection.

Every wildfire has behavior differences. The rate of spread and flame lengths change from the high extreme to the low. They occur even though fire danger conditions are stable and unchanging. Some changes are due to transformations in the weather; but fire can change when weather does not. Changes also occur because of the differences of fuel types. Changes occur because the topography features differ, but the fire behavior changes also occur when topography does not change. Each location where a wildfire burns over has variables that create changes in the fire’s intensity.

In order to survive, today’s firefighter needs to make the complex seem simple. The changes in the fire intensity, rate of spread, and flame lengths are factors that concern the firefighters. When it possible to anticipate changes, it makes a much safer situation.

I once attained fire behavior classes that listed all the things that change the behavior of the fire. I felt as if the instructor opened a bag, dumped the contents into my lap and said, “You sort it out.” I could never hold all these things in my mind and fight fire too. So let’s try another way; let’s isolate the force that is ruling the fire and simplify the complex by listing and naming the major forces that have the controlling power over a fire.

Fire Classifications – An Aid to Tactics Selection

One or more of these three conditions changing causes fire behavior changes:

WIND force and direction acting on the fire

FUEL changes of type or flammability in the path of the fire

TOPOGRAPHY variations in the path of the fire including hot and cool aspects

Often two conditions combine to fuel the fire behavior. Classifying the ruling condition helps to simplify the generation of good fire behavior predictions. This allows the tactician to ignore factors that are irrelevant to the fire intensity, and to isolate and focus upon the few pertinent factors that are causing the changes in intensity.

The fires running before a Santa Ana wind condition are wind-driven fires. Fires burning in old timber, as that in northern California in 1987, seemed to defy topography; they were fuel fires. Many fires, including prescribed burning operations, are affected mostly by topography, and so are termed topography fires.

What tactics are best used against these three fire types?j

Fighting Wind-Driven Fires

Wind-driven fires are fires that react primarily to the wind force, running before the wind, but not changing significantly because of variations in fuel or topography. Wind forecasts are the key to predicting wind-driven fire behavior. Wind is actually the result of more than a single force. It is necessary to learn about these forces and to understand how reliable or unreliable the wind force and direction is. If the wind direction changes, the fire flank can become the fire head.

Note how the fire is out of alignment with slope, in smoke shaded fuel and in alignment with wind. The dominate force is wind.

When a fire is dominated by wind, the preferred tactic is to anchor the heel and establish fire lines along the flanks of the fire in direct attack. Be quick to reassess or predict when the wind will cease to dominate the fire. Another condition will “take over” and the tactic will need re-evaluation.

Fighting Fuel Dominated Fires

Fuels fires are those fires that burn into fuels of a type and in such a condition that when they burn, such intensities are created that control is not possible until the fire burns out of that particular type fuel bed.

The fires during 1988 in Yellowstone Park were difficult to control because an extensive drought had dried old, aged lodgepole stands. Fire burning in these fuels released enough energy to create a micro-scale weather envelope extending into the unburned areas some distance.

It was on the Klamath north front that we coined the phrase “The dew won’t do it.” Even though there was dew on the fuels in the proximity of the fire, the dew could not form on the fuels near the fire edge because of the existence of the fire’s envelope.

In observing the fire behavior on a fuels-type fire, it is quickly evident that the topography and weather are secondary factors.

One morning I noticed that my sleeping bag was wet from dew, but still the fire continued backing down slope as it had in daytime. Why? It finally dawned on me that the fuels near the fire were within the fire’s environment. This is what Mr. Countryman was writing about! The fire’s environmental envelope prevented dew from forming on the fuels within the envelope.

Illustration of a Fuels Dominated Fire

“Fuels fires” are those fires that burn into fuels of a type and in such a condition that when they burn control is not possible.

Sometimes the envelope extends over the control lines and those areas become untenable for firefighters. This was the situation on the 1988 Yellowstone fires. Planned tactics required suppression forces to make a stand in a large safety area, but failed to be mindful of the extent of the fire environment envelope in which the firefighters could not effectively work. The peak of the flammability curve is the prime time for large energy releases and extended environmental envelopes.

To predict fire behavior under these conditions, get out the fuel type and age class maps. These maps become the key element in prediction.

Wind forecasts are important because a change in wind will dictate the direction of spread and spotting distance. Observations of the extent of the fire’s environmental envelope should be included.

The most successful tactics to use under these conditions are burnouts from indirect fire lines in lighter fuels, or burnouts from natural barriers. If wide lines on the flanks are not possible, then back away from the fuel type that resists control, and burn out the flanks or wait for weather conditions to modify the fire behavior and then cold trail.

I have seen crew’s loose line day after day, only to receive orders to try again. This reveals a failure to understand the fire behavior and the capability of the crews to hold the line. If a tactic (such as under slung line on a timber fire) is not successful during one shift, it is important to ask how that same effort is expected to be successful on the next shift?

That is a question that begs to be answered. A plan that is written into a division assignment sheet and already in motion is tough to alter at a 5:00 a.m. briefing. New information is most valuable when delivered on the front end of the planning timetable. I have found there is another often used tactic that doesn’t consider the firefighters best chances of success: that is what I call the political tactic. This tactic is for show only. It is used to salve the public or media. Such tactics, while useful for this limited purpose, will frustrate every firefighter who wants to win.

Fighting Topography Fires

The topography fire is a fire where the major influence on fire behavior is the variations in topography. In other words, fire behavior intensity changes can be predicted if you understand the topography’s affect upon the fuel’s flammability, winds and the fire spread potential. To make predictions for this type fire; they key is the topography. Break out the topography map or the relief map that I prefer to use. Draw the fire perimeter on the map

The topography fire is a fire where the major influence on fire behavior is the variations in topography.

Knowing the topographic influence on the fire’s behavior is a key element to making good fire behavior predictions. Many fires fall within this category. Prescribed fire is one.

While observing the fire behavior ask yourself, “What is causing the variations in fire behavior?” Is it weather changes, fuel differences or topography variations? Chances are if weather and fuel changes are not the driving forces, it is a topography fire.

Highlighting the Topography Fire’s Variable Potential.

Topography fires are one type fire where the effects of variations of fuel flammability are quite apparent. In this case, the time of day, aspect, and position of the fire on the topography are the key ingredients in predicting fire behavior changes.

It was in September during the fire season of 1987 that I first utilized the hot slope map. I was assigned to the 1,200-acre Mooreville fire. It was in Plumas County on National Forest land, but a California Department of Forestry overhead team was in command.

I was called out from three years retirement to function as this team’s Fire Behavior Analyst. I had no kit, no computer, and was confronted with an uncomfortable situation. There were fires all over the state, a bad fire season. I arrived at the command post early in the morning and introduced myself to total strangers. I asked Ben Stuart, the Plans Chief, for a contour map of the fire area and had short conversations with others in Plans. I looked over the map fire situation and saw the fire was in good position to make a run on a long southwest-facing slope.

I inquired about the control tactic and assignments on the division and found it was not beefed up at all. I realized that the team did not see the potential of this fire; I needed to communicate quickly. Finding a yellow highlighter marker, I began coloring the afternoon hot slopes on the map. I colored the west, south and flats yellow. This was the first fuel flammability map or hot slope map that I know of, and it was vital to communicate the pending situation to the overhead personnel.

I met with the Incident Commanders, Bill Sager and Frank Bates, and directed their attention to the hot slope map. I pointed out that the winds would align with the up slopes and from noon to four in the afternoon there was potential for the fire to double in size if it were allowed to relocate to the base of the slope.

I named a yellow highlighting pen a Yellowommeter and used it to illustrate the hot aspects in front of the fire.

The Incident Commanders immediately took the steps that would best prevent the escape of the fire to the hot slope that I’d colored yellow. I had done this without seeing the fire firsthand, and only using the map and resource information. I hurried to see the fire from the ground and air to confirm my suspicions. A field recon verified my predictions. The crews held the fire on cold slopes and prevented the worst-case scenario from occurring. Later I spent some time discussing with Incident Commander Bill Sager the effects of radiation intensities on various aspects. On one occasion, Bill asked me to fly to another fire that had just been reported in the vicinity. We jumped into a CDF helicopter and flew over the fire. There were almost no resources on the fire at that time.

Bill asked me to tell him what the fire would do. I thought, “Now you’ve done it, you’ve set yourself up for a fall!” But I proceeded and did my best to predict the potential of the new fire. I saw the fire was near the base of a long south slope and little was being done to stop the spread in that direction. The other parts of the fire were heading toward cold afternoon slopes or were backing into the wind. I told Bill that if control were not established on the north end of the fire, it would run up the hot afternoon south slope by noon of the next day.

Sure enough, the following day there blossomed a large convection column visible from our fire area. Bill confirmed what I predicted. The fire had run the south-facing slope and was really cooking. Before this fire siege was to be over, I had spent over 20 days on Bill’s team and was to spend another 20 days on other Northern California fires. It was here on the fire ground that I began the development of this fire prediction system that I now teach others.

Tactics for a topography fire run the gamut. Direct attack, indirect attack, parallel line construction, backfire or burnouts. All tactics may be safe and effective, or many tactics could become unsafe in some location or for a particular period. This is one reason that topography fires are so dangerous. The fire is constantly changing its position upon the topography just as time is changing. Fuel flammability’s are not constant for long, and they change from hot to cold on various aspects. Fuel temperatures vary from air temperatures in shady locations and become 150-degree fuels in the sun.

As the shadows shorten on the aspect, the various aspects reach their extreme flammability at different times of day. As the shadows lengthen, the fuel temperatures become closer to the same temperature as that of the air. Under these fire conditions, tactics may need to be changed because of time, or because of the location of the fire on the topography.

Whenever topography, weather, time of day and position of the fire on the topography changes, tactics should be re-evaluated to ensure they remain safe and efficient.

Copyright © 1991, 2016 by Doug Campbell.