Mission & Vision Statement:

(M) Saving former fire management work

(V) To allow others to utilize improvements

The following post describes the TRAP program developed by Doug Campbell in the 1980’s.

OJAI RANGER DISTRICT’S FIRE MANAGEMENT PROGRAM

TRAINING, READINESS, ACCOUNTABILITY AND PROFICIENCY (T.R.A.P.)

Fire management on the Ojai RD has developed a program that is useful to the Ranger, the DFMO and the module leader and crew personnel. The program displays the ingredients or the guts of the Fire Management Program.

Targeting the Problem:

Fire Management in a nutshell:

Hiring green people, putting them into various fire modules to protect the National Forest from wildfire damage is the reoccurring operation of fire management.

At first the crews are liabilities. Developing them into a cohesive protection force, following the guidelines of policy, forest objectives, and a Ranger’s changing focus is not a science.

An old Chinese proverb is that “vision without action is a daydream and action without vision is a nightmare.”

With a shared mission and vision statement proper accountability can create a better organization.

Journeymen fire technicians usually strive to gain the maximum protective capability and provide the margin of safety required early in the season. Rangers and management staff often overlook the value of and the need for the investment in training to accomplish this.

TRAP is a program that displays the ingredients of a sensible fire management program and shows the relationship of influences upon that program. The program helps to foster an attitude of shared responsibility from the Line Officer and Staff to the firefighter crew-person.

At the start of fire season the Forest objective is to require proficient fire modules by July first. The Ranger wants a commitment from fire modules for project work during the formation of the modules. The DFMO knows there is not much accountability for the proficiency of the fire module but that the ramification of an under-trained crew of a wildfire could be life-threatening or the crew could easily become over-extended beyond their capabilities and fail to accomplish the assignment; thereby adding acres and threats to the crew.

The project on the other hand, is very visible and the Ranger can easily see accomplishment, or the lack of it.

The trade-off of readiness for a project target is eminent. The fire training and readiness is at a disadvantage in competing for priority.

The right thing to do is obvious to the technician. The Ranger cannot see the concern because the background required visualizing the complexity is normally many years in the business of reading crews and fighting fires with them.

This kind of barrier to communication can be overcome. The ranger has little time to spend learning the intricacies, and needs a quick way to evaluate the whole situation so that he can make a good decision that the DFMO will accept without feeling he is responsible for an impossible situation.

Implementing the T.R.A.P program:

- Display fire management targets by month. This includes Forest and District objectives that management requires. Targets should show when the new crew persons are hired, where full proficiency is desired to provide for safety and protective capability desired.

- Display the investment training time required to accomplish the goal in crew days by the month.

Example: For June,15 crew days in training, 5 days for projects.

As time goes by, the desired level of proficiency is attained, the project capability increases and the training investment decreases. Training investments obligate maintaining the proficiency levels of acceptability.

- Display the training program in enough detail to show the academic course of lessons needed and the required investment.

Footnote: Proficiency is measured and graded by the module leader, the AFMO and DFMO and S.O Fire staff officer. Grading the drill program assures modules work together and attain proficiency in knowledge and skill to meet the standard of the drill.

There is a need to display the impacts of things that affect the program. There should be room on the display to show impacts to the time line of training. Fires, accidents, personnel change and other impacts that identify the units responsible should also be shown.

Designing the drill program for the modules needs individual development so what we designed will not be included here.

Some of the cost analysis also is omitted.

Some of the outputs of TRAP are listed:

- New nozzles for engines to allow the GPM available from the units.

- New hose lay developments going from rolled hose to pre packaged quick deployment designed.

- More cooperation from Line officer to District Fire staff.

- Forest Supervisor including Fire program in their goal.

- Better understanding of the needs and proficiency standards for all modules.

- Transferred and improved on the Angeles NF by Will Spyrison DFMO.

Ojai and Stan Delong created the first TTO academy as another effort to educate drivers of engines and improve their skills.

Some impediments to deal with.

- Limited authority of module leaders and fire staff to weed out misfits by firing.

- No standard personnel evaluations to hold employees to and

- limited hiring authority for the fire staff.

- After program managers retired the program was not carried on.

- The FS has no capability to utilize the improvements the field officers have developed.

- The budget stopped the fire group from working on trails, roads of recreation projects because fire was not funded to work on other projects.

Fire Prevention

The development of the Preventability index.

Create a different fire cause chart instead of picking one cause because it is required. The cause being selected for the fire report without proof is questionable.

This concept suggested by Dennis Ensign was utilized in the Ojai Annual Fire Prevention Plan. The concept was to identify and prove the fire cause and if unproved select a value for unknown.

The idea is to know how preventable each cause is. Some causes are treated by prevention and others are not, but all have an assigned prevention cause value. The prevention plan listed known causes on various units assigned to prevention personnel. The mission for prevention is to make causes known and do work that would add prevention efforts to the known causes on each unit. The vision was to lower the value of the combined preventability index to be more effective in prevention efforts. The P-I was lowered on the Ojai District and kept track of over the years. This program required that each prevention unit have a work program that would accomplish the mission.

The chart below is the record of achievement of fire prevention work during 1980 to 1983.

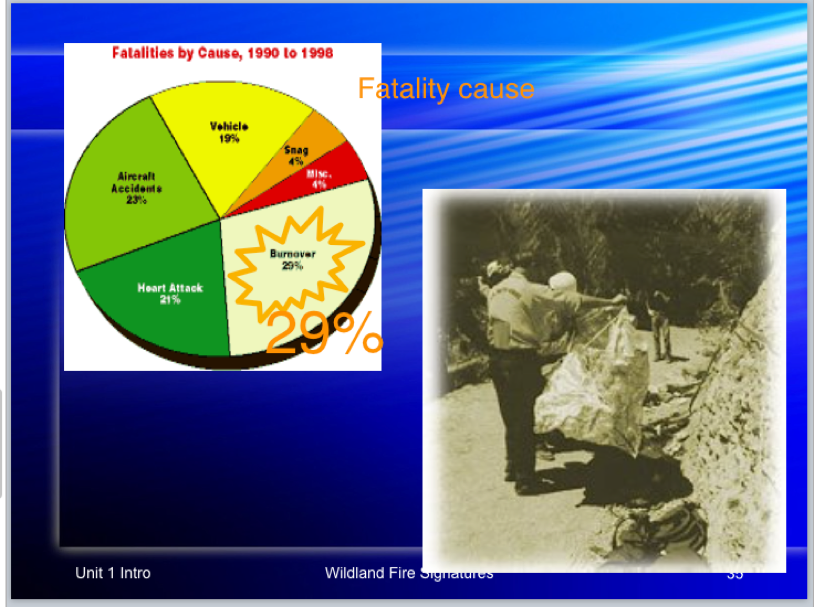

Taking an unusual action for an FMO I began teaching the personnel. The highest priority was teaching how to read the wildland fire and make decisions to avoid entrapment. Twenty-seven of my co-workers had been burned over during my time in fire. Working from Ed Hellman’s Micrometeorology course and my background of meteorology training from time in the US Navy were the basis of the subject. Fatal fires were the Decker fire on the Cleveland Forest in 1959 and the Loop burn over in 1966, both involving the El Cariso Hotshot crew. The subject goal was to make the unpredicted into a predictable situation.

Accepting this subject in the Hotshot and Helishot modules was made difficult because of their clannish nature. This subject was the beginning of the course of training now titled The Campbell Prediction System. This course was taught in the State fire Marshall Academy as well as throughout the US States and Canada and Spain. The program is now presented in Europe in 8 or 9 countries. At this time thanks to a computer programmer named Bruce Schubert, The Campbell Prediction System book and articles are on cps.emxsys.com. NASA became involved with Bruce and has hired Bruce.

My thanks and appreciation goes to Al West who hired me and to the following Rangers who encouraged and allowed me to run the fire group as I did

Al West

1966-1971 Ojai District Ranger

1976 -1979 Los Padres Forest Supervisor

District Rangers: Al West, Art Carroll, Dick Ober, and Walt Schloer

During My time 1970-1984

Many folks who worked with me and carried out the mission are appreciated and never forgotten.

By Doug Campbell

URL: cps.emxsys.com

8/11/2018

805 646-7026